Methodology is the key to Visual Impact Assessments

We’ve updated our VIA process and mapped out a clear path forward for projects

Visual impact continues to be an evolving space for the urban development industry, and with no firm methodology in place, this enables the industry to have different views on how it is best approached.

Unlike other assessment processes such as analysing sun access where the impact can be quantified, visual impact is inherently subjective. What one person thinks is acceptable, another may not. As noted by the Land and Environment Court of New South Wales (the Court) (Rose Bay Marina Pty Limited v Woollahra Municipal Council and anor [2013] NSWLEC 1046), the key to addressing this challenge is to adopt a rigorous methodology. This is where visual impact assessment (VIA) comes in.

Key implications

The issue is that VIA is very complex. While the process for addressing impact on sight-lines from private property is well understood through Tenacity (Tenacity Consulting v Waringah [2004] NSWLEC 140), addressing of impact on the public domain – which is arguably more important – is less understood. To further complicate this process, while some consent authorities like the City of Sydney have a relatively clear policy on visual impact, many other councils do not. Due to this, regard is to be given to an array of Land and Environment Court planning principles. While these include the well-known Tenacity for private views and Rose Bay for public views, this can at times also include other, less well known principles such as Project Venture (Project Venture Developments v Pittwater Council [2005] NSWLEC 191), Veloshin (in the case of Star City) and the veritable Davies judgement (Davies v Penrith City Council [2013] NSWLEC 1141).

The pathway forward

We’ve been providing expert advice to clients on VIA issues for over twenty years. During this time, we have developed and refined our VIA methodology through involvement in complex urban development projects such as Barangaroo South and other iconic locations such as Mt Wellington in Hobart. We have also recently undertaken a comprehensive update of our assessment process to add even greater rigour. Collectively, we are well placed to simplify this complexity and map out a clear pathway forward for projects.

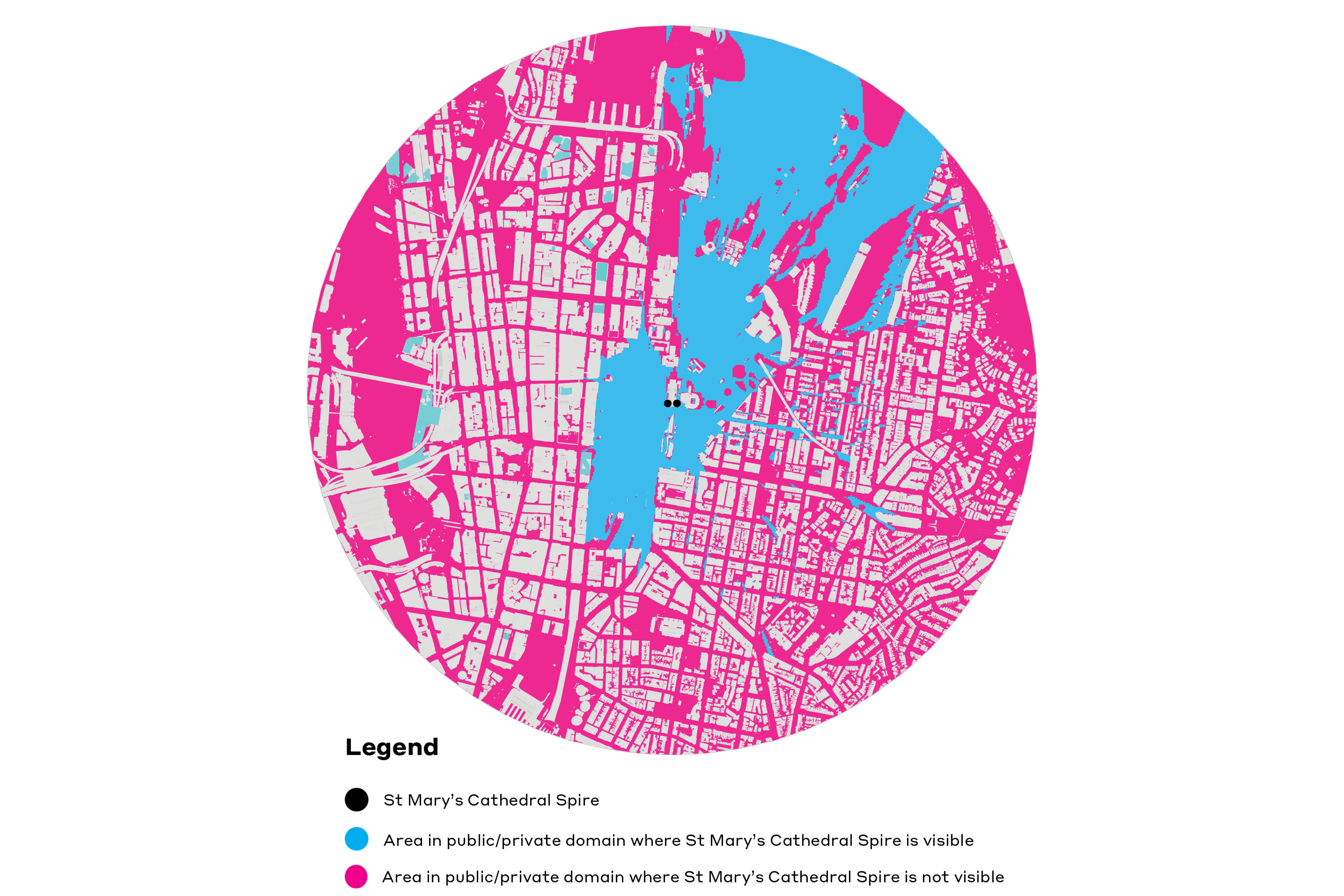

Mapping visibility

One of the first steps in doing this is to understand from where a proposal may be seen. Under the international standard Guidelines for Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment, this is called the ‘Zone of Theoretical Visibility’. This has the benefit of focussing effort, with areas from which it may not be visible usually being excluded from more detailed assessment. The below figure shows how this may be undertaken. We have taken a point at the apex of St Mary’s Cathedral and extended it in ray form towards the ground and outwards in a 360-degree arc. Where this ray hits an element in the landscape such as a hill or building, it is blocked. It is typically safe to assume that anyone standing in a street or park in the shadow of this element cannot see the apex of St Mary’s Cathedral. While ultimately a full visibility assessment needs to be undertaken manually by a trained and experienced expert, the use of computer assisted technology such as this can add great value, and speed up the process.

An evidence-based approach

Once this process has been completed, VIA can proceed. This in its own right is complex, folding in a number of theories (e.g. evolutionary vs cultural), approaches (e.g. objectivist vs subjectivist) and practice. Based on our in-depth understanding of the NSW planning system, we’ve developed an approach that enables characterisation of the landscape as an object. This provides a strong basis for lessening inherent subjectivity, and informing more evidence-based, objective judgements about impact.

Line, shape, form, colour and texture

While there a number of ways in which we can do this, one of the core ways is through reference to formal aesthetic principles. Similar to artwork such as painting, this breaks down a view by line, shape and form, colour and texture. The next image shows how the southern façade and the visible setting of St Mary’s can be analysed in this manner. The main benefit here is that it can be used to not only communicate to decision makers, but also to help shape the location, orientation, scale, form and design of new development to reduce impact. In a heritage setting such as St Mary’s, it can also be used to help guide a more sympathetic heritage response. Clearly in this way the value of VIA is multi-faceted.

Our VIA offering

We’re currently advising several State and local government agencies and major private sector developers on VIA matters. We’ve seen first-hand how VIA, when applied early on as part of a design development, can greatly improve the likelihood of positive development outcomes.

If you would like to discuss VIA further, please contact our expert Chris Bain – Director, Planning.

Related Insights

How Immigration Shapes Housing Choices in Victoria?

NSW Low and Mid-Rise Housing Reforms

NSW Government Releases Industrial Lands Action Plan